by Bob Gilmore

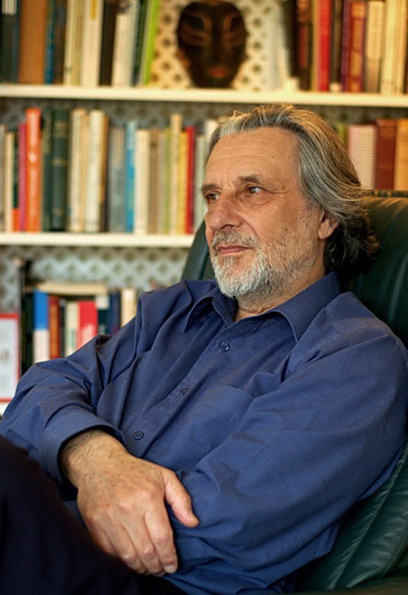

Frank Denyer is an English composer whose brilliantly coloured and imaginatively rich compositions fall between several and into none of the accepted categories of contemporary music.

Born in London in 1943, he was a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral by the age of nine, the director of the experimental music ensemble Mouth of Hermes in London at the age of twenty-five, and a Doctoral student in ethnomusicology at Wesleyan University, Connecticut at the age of thirty. He has lived and worked in east Africa and India.

Denyer’s music is distinguished by a keen sensitivity to sound. Each of his works is written for a unique combination of instruments, more often than not a combination that no composer has dreamed of before. Each work finds its own individual form, laying down the path for its journey as it proceeds. In some cases even such basic musical materials as the scales and the tuning system are invented from scratch.

This music is handmade in every detail; it is engaged in a complex process of affirmation and negation, accepting no easy solutions.

For Denyer, a fine pianist who has composed not one note for his own instrument since his student days, the whole question of musical instruments is a central one. His compositions present an astonishingly varied array of sound sources – new instruments of his own invention, adapted instruments, instruments of non Western traditions, rare or virtually extinct instruments, and conventional Western instruments. This whole concern with what his friend Morton Feldman called ‘the instrumental factor’ is not a postmodern mixing-and-matching of instruments from different ‘ethnic’ traditions: rather, his work suggests that all instruments bear the imprint of the tradition of which they are a part, whether that tradition be nascent, mature or decaying, and that at the beginning of the twenty-first century we cannot afford to be complacent about which musical traditions we consider to be ‘ours.’ Neither is his music that of a composer making do with ready-mades or whatever lies to hand (like Cage’s percussion ensemble works of the 1930s and early 1940s). Nor, at the other extreme, does one have the sense of the composer gradually assembling an instrumentarium of his own, creating the illusion of an alternative musical universe (like Harry Partch): for one thing, Denyer’s assembly of new instruments hardly ever plays together; for another, they rarely recur from one work to the next – each new composition wipes the slate clean and starts afresh. The instruments are like flowers that suddenly spring up between the cracks in a wall; they seem to be there because the opportunity has arisen for them to exist, to fill the gaps between isolated islands of instrumental sound.

Denyer’s concern with musical instruments can also be seen as a metaphor for the larger question of what can be salvaged, artistically, from the chaos of civilization as we begin our new century. Compositions like A Monkey’s Paw (1987-88) and Finding Refuge in the Remains (1992) confront this central issue – the sense of new life emerging from a morass of dead or decaying matter – an urgent issue for him both compositionally and culturally.